* N.B. this article expands on last week’s podcast *

Practitioners studying yoga texts face a dilemma – should they try to understand them in historical context, or attempt to align them with contemporary priorities?

Textual scholars mostly opt for the former, whereas yoga teachers tend towards the latter. The two interpretative frameworks are hard to combine. Scholarly analysis is usually rooted in critical distance from yogic teachings, rather than guidance on how to apply them, so readers seeking practical insights turn elsewhere. The only problem is that popular authors are often misleading about what texts say, reinterpreting ideas so they sound more appealing to modern audiences.1

Academic responses to this trend can be scathing. To quote a 2013 article by the Indologist Philipp Maas, “public interest in yoga is, at least in part, channelled and satisfied by amateurs and self-designated representatives of ‘the yoga tradition,’ who propagate religious and partly right-wing Hindu fundamentalist ideas disguised as knowledge”.2

Things have nonetheless improved in the intervening decade. Scholarly work has become more accessible – via proliferating course platforms, podcasts and talks, as well as open-access publishing – raising public awareness of its discoveries. But despite the inclusion of more accurate materials in yoga teacher trainings, misconceptions abound about historical facts, from the unprovable notion that yoga is 5,000 years old to the related assumption that authenticity depends on antiquity.

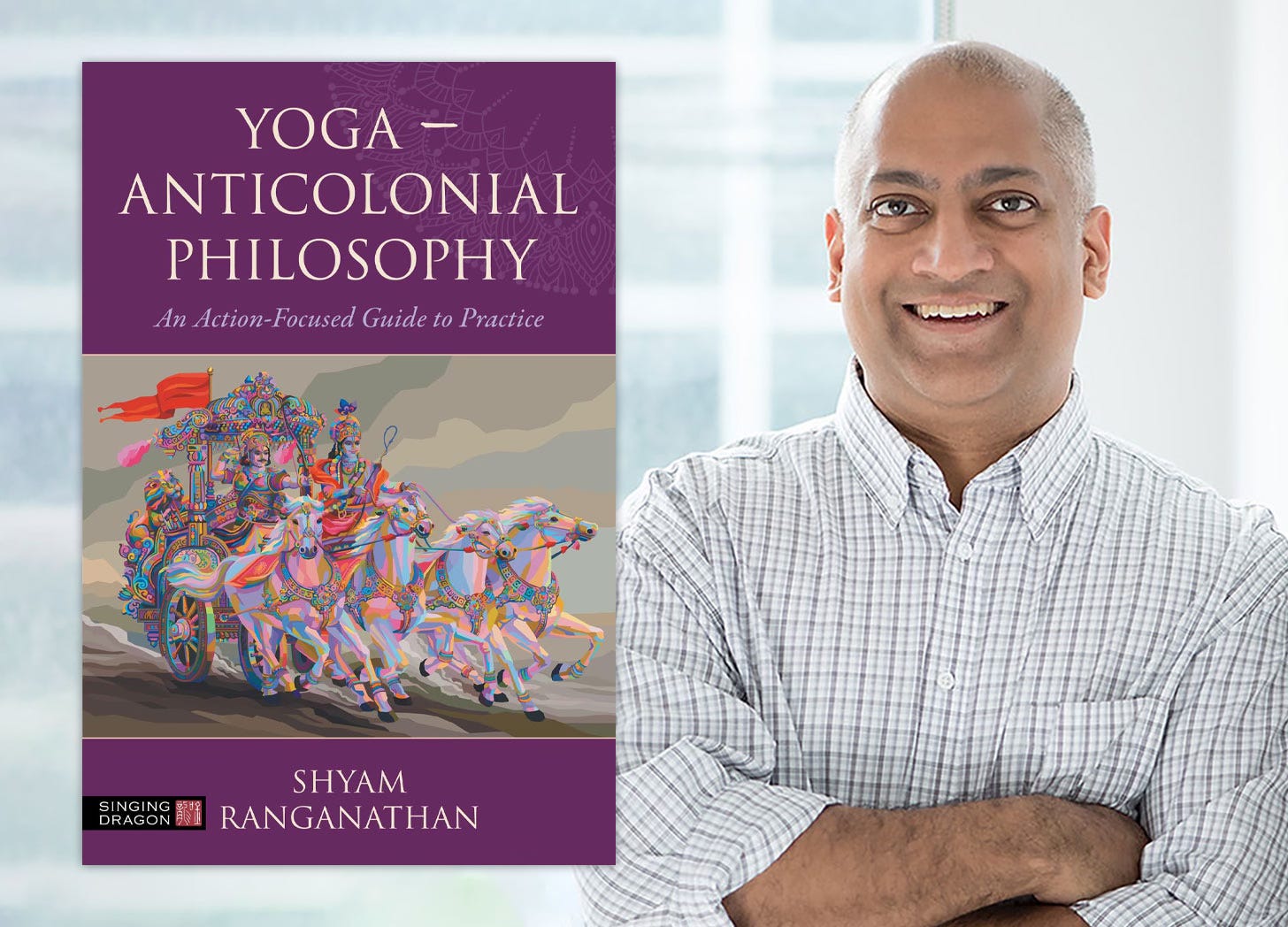

Although yoga has evolved into many varieties over the centuries, with ideas and techniques being widely borrowed and recontextualised, concerns about exploitative patterns of commodification – labelled “cultural appropriation” – have heightened Western interest in respecting tradition. This is often presented as part of a process of “decolonisation”.3 The title of a recent publication by Shyam Ranganathan channels these themes. Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy is not an academic book, though its Canadian-born author teaches courses on philosophy at York University in Toronto.4 Instead, the cover bills it as “a comprehensive guide for any yoga teacher or trainee”, with “discussions on the precolonial philosophy of Yoga” and “the impact of Western colonialism” on yoga scholarship.5 These are important topics that deserve consideration, but Ranganathan’s take on them makes strong claims that require investigation in themselves – particularly given his influence on practitioners.6

DISPUTED APPROACHES

The book is in some ways an extension of his 2008 translation of Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, which outlines the basis of his critique.7 “Scholars of Indian philosophy have typically gotten the content of Indian philosophy wrong,” Ranganathan writes in that earlier work.8 Drawing on his PhD research,9 he argues that translation of philosophy requires broad understanding of “key philosophical terms” across many traditions – not expertise in Sanskrit, or the history of texts and their cultural contexts.10 “Linguistics and philology are thus at best ancillary to the body of knowledge necessary to translate a text of philosophy,” he says,11 because the aim is to articulate “a philosophical perspective that explains the text”.12

Ranganathan seeks to do this by highlighting ethics. “If we were to read Patañjali as he is often translated,” his Yoga Sūtra book objects, “we would have to conclude that he is interested in a dispassionate, abstract spiritual exercise, geared simply towards the personal goal of liberation.”13 In his view, however, Patañjali presents “a moral theory chosen for its social implications”.14 And since the clarity of mind that sets one free requires “one’s actions to be made morally perfect” in the process,15 a liberated yogi can act as “the perfect agent of helpfulness” – an enlightened being unhindered by self-centredness and harmful behaviours.16

Attractive as this outcome might sound, it is not actually described in Patañjali’s sūtras – the pithy Sanskrit aphorisms used to share ideas in a range of Indian disciplines. The wording of the text promotes inward focus not worldly activity, but Ranganathan’s method is not strictly literal. “I began with the premise that Patañjali was attempting to articulate a novel, logically and practically coherent philosophy”, he says, while assuming that “the task of the historian of Indian philosophy is to discern how a moral theory plays itself out in the system that a philosopher elaborates”.17 So his aim was to develop a theory about Patañjali’s system, then to use it as a guide for an English version, unfazed by his own rendition of Yoga Sūtra 1.9: “Verbal delusion arises when words do not track (real) objects.”18

His creativity in Sanskrit translation is mostly transparent. He breaks down the text of sūtras word-by-word, revealing to a reader how he reaches his choices. Sometimes, he selects definitions that – while found in dictionaries – seem at best tangential. For example, Yoga Sūtra 1.13 says practice is the effort to steady the mind, which he renders as: “Abiding (in the true nature of the self) is the result of the will’s determination to stay in that stillness.”19 He provides his rationale in accompanying notes, saying: “The practice of yoga is a direct result of will. Moreover, the presupposition here is that it is the person who is spoken of as the one exercising will. Yoga is thus the result of the puruṣa’s own efforts.”20

This is where things get complicated. The word puruṣa – literally a “person” – refers to the innermost conscious self, which is distinct from the body, the mind, the senses and the world. In Patañjali’s dualistic system – based on Sāṃkhya metaphysics – everything else is part of the material realm called prakṛti. Discernment of the difference between puruṣa and prakṛti leads to liberation. This requires mental clarity. Once the mind is steady and clear, it can reflect the light of awareness back on the puruṣa, which thereby perceives itself.

However, to quote Vācaspati Miśra, a tenth-century commentator: “Although the self is certainly self-illuminating, it does not perform any act”, and thus has no will.21 Like almost every other pre-modern commentator, Vācaspati discusses the sūtras alongside an earlier explanation (bhāṣya). This is traditionally ascribed to Vyāsa, whose name means “compiler”, but manuscripts show that both texts were transmitted together as the Pātañjala-yoga-śāstra – and since they were composed at around the same time, some scholars have concluded that they had the same author.22

Whoever wrote the first commentary, it agrees with Vācaspati, defining puruṣa as “ever aware” and “not mutable”.23 Both are therefore aligned with the foundational text of Sāṃkhya philosophy, the Sāṃkhya Kārikā, which says puruṣa is “a spectator and inactive”.24 Ranganathan disregards this as irrelevant. “One gets the impression,” he writes in a critique of yoga scholarship, “that there is no philosophy of the Yoga Sūtra: just commentaries all the way down”.25 Instead, he advocates “a faithful engagement” with the text that “involves no deference to commentarial authority but a direct interest in yoga”.26

To justify his view, he cites sūtra 1.29, which refers to puruṣa as cetanā (meaning “consciousness”). Ranganathan adds two more definitions – “intelligence” and “volition” – and says: “Patañjali intended all of these significances”.27 Using cetanā to indicate will is a Buddhist idea, and Sanskrit-English dictionaries do not define it as “volition”,28 though some ancient forms of Sāṃkhya do link it to activity that sets the world in motion.29 To convince a lexicographer, Ranganathan would need to show examples of similar usage in Sanskrit texts from the time of Patañjali, but he provides none.30 In any case, “consciousness” seems more plausible, because the synonym used for puruṣa elsewhere is “seer” (draṣṭṛ).31

The whole disagreement boils down to whether Patañjali promotes renunciation or, as Ranganathan puts it, “social change that is activistic”.32 Although the sūtras are occasionally ambiguous, the commentary is clear. For example, expanding on sūtra 2.40, which mentions “disgust for one’s own body”, it says a purified yogi “becomes unattached to it, an ascetic. Moreover, there is no contact with others. Seeing the body’s true nature, he desires to give up his own body”.33 This reflects the text’s aim of detachment from matter. Its final sūtra (4.34) describes “isolation” – the liberated state of kaivalya, which leaves “the person to abide in their true nature”.34 If puruṣa has no agency, this might resemble a catatonic trance. Results of that sort are described in other texts, such as the fifteenth-century Haṭha Pradīpikā, whose compilation of physical methods concludes: “The yogi who is completely released from all states and free of all thoughts remains as if dead.”35

UPPING THE ANTE

Ranganathan’s new book is a radical update to his thesis. Reframing kaivalya as “autonomy”, he says: “Yoga is about being an independent individual”.36 The alternative is to be colonised, and to perpetuate colonisation: “Without the original practice of Yoga, that teaches us how to be aware of and protect our individuality from external influences, we end up participating in Western colonialism by passively endorsing and using its beliefs”.37 He links this distinction to sūtras 1.2–4, which describe how mental stillness enables puruṣa to dwell in itself, while mental activity stops this from happening. As such, Ranganathan suggests, yoga amounts to “being responsible for sorting the data so that one can appreciate the options” and choose liberation.38 Or to put it more simply: “Logic is Yoga.”39

The corollary to this is that challenges to his conclusions are a) illogical; b) not yoga; c) colonial. The book’s index contains more entries under “colonialism” and its variants than any other word. Meanwhile, Philipp Maas – one of the world’s foremost scholars of Pātañjala yoga – is said to be “ignorant” and reliant on a “methodology of narcissism and colonialism” due to his “incompetence” in “reasoning and thinking”.40 Vast swathes of the book are given over to rants about “Western Indology and Yoga Studies”, with academics in these fields compared to supporters of Donald Trump’s refusal to concede defeat in the 2020 U.S. presidential election.41

Much of Ranganathan’s rhetoric functions reductively. He outlines a binary that mirrors the reasoning of racial justice activists, positioning himself as a rational campaigner against “racist features” of academia.42 This manipulates legitimate concerns about potential transgressions to promote his ideas, while implying that critics are driven by bigotry. In How to Be an Antiracist, a bestseller published shortly before the 2020 murder of George Floyd and the protests that followed, Ibram X. Kendi writes: “One either allows racial inequities to persevere, as a racist, or confronts racial inequities, as an antiracist. There is no in-between safe space of ‘not racist’.”43 Similarly, one either agrees with Ranganathan or enacts “White Supremacy” by using “the methodology of Western colonialism”.44 Meanwhile, “anticolonial, activist research will always be accurate,” he asserts, “as it involves using logic to tease out implications and thereby circumvent our ego”.45

Ranganathan calls this process “explication”, or “rendering explicit what the Yoga Sūtra has to teach us via logic”.46 Having established the principle that “valid arguments can be comprised of entirely false propositions”,47 he proceeds to advance some, unhampered by facts. In this logical parallel universe, constructing a theory supported by inference trumps all alternatives, becasue “if we mistakenly believe that the truth is the most important aspect of an argument, then we end up endorsing nonsense as though it is logic”.48

This leads to a string of nonsensical statements. Other “modes of explaining yoga are foreign to the South Asian tradition”,49 Ranganathan argues, yet his own “explication” has no trace in traditional sources. Although the scholars he dismisses quote those sources, he rejects their work as irrevocably tainted by “Western beliefs”.50 Meanwhile, one Indian translator of the sūtras and commentary, Hariharānanda Āraṇya, was so convinced of the renunciate focus of Patañjali’s yoga that he spent his last two decades sealed up in a cave.51 In Ranganathan’s assessment, all textual scholarship is “interpretation” – which “violates logic, is ignorance, and creates ego”52 – yet he ignores all the evidence supporting its conclusions.

“When we interpret,” he writes, “we can only appreciate what we believe, and anything that deviates seems like a threat to our outlook, which we confuse with ourselves”.53 Might this diagnose his own litany of gripes about “marginalization” by those who disagree with him?54 Or would inferring as much be interpreting? Either way, his reasoning explicitly incorporates Western philosophy, which he otherwise derides for underpinning colonialism. “To understand what Patañjali wrote,” he explains, “our translation and explanation must be informed by a certain principled and disciplined cosmopolitanism and internationalism that is most often missing in traditional settings”.55 As a result, “we must transcend the narrow focus of the Indian tradition, for the philosophical text is not tradition specific”.56

This cuts to the core of his clash with Maas, who regards the explanations provided in commentaries as “indispensable for any appropriate interpretation of the frequently enigmatic sūtras in their contemporary religious, philosophical, and cultural contexts”.57 However, this depends on an interest in history. As Maas has noted elsewhere, the decontextualised “text-immanent approach to the Yoga Sūtras was indeed used frequently to project anachronistic ideas upon this text”.58 Interesting as those may well be, they have little to do with Patañjali’s yoga and should therefore be distinguished from it.

BACK TO BASICS

Ironically, Ranganathan’s translation of the Yoga Sūtra makes occasional use of the original commentary – for example, in interpreting two lists of four words in sūtra 1.33 to promote “an attitude of friendliness towards the pleasant, of compassion for those who suffer, of joy for the meritorious, and of equanimity towards the unmeritorious”.59 Since indifference to wrongdoers jars with his overall activist message, it seems an odd choice. The sūtra itself is unclear, so Ranganathan could have overlooked the commentary’s pairings of attitudes with characteristics to draw inspiration from Buddhist traditions, which apply all four qualities to all beings – as in “loving-kindness” meditations that share benevolence with everyone from friends to adversaries. That might have led him to translate the sūtra like Pradeep Gokhale, a scholar of Buddhism, who writes: “The mind becomes tranquil by cultivation of friendliness, compassion, gladness and equanimity (or indifference), which have happiness, suffering, merit and demerit (respectively) as their objects.”60

There are also signs that proficiency in Sanskrit is not Ranganathan’s forte. To take one example, his version of Yoga Sūtra 3.29 – which he numbers 3.30 due to including an earlier line of commentary as a separate sūtra61 – suggests that focus on the navel “provides comprehension of the arrangement of the cakra-s in the body”.62 This misreads grammar (nābhi-cakre is a genitive tatpuruṣa in the locative singular, so “on the circle of the navel” means only one cakra), along with yoga history. Ranganathan says “cakra-s of the body are energy centres that correspond to emotional-psychological planes”,63 but this is Western New Age thinking.64 The original descriptions in Tantras, which post-date Patañjali, use cakras as blueprints for visualisation, so they need to be meditated into existence.65

Meditation is really the core of Patañjali’s method, yet Ranganathan barely mentions it. Instead, his focus is on kriyā-yoga, the “yoga of action” combining austerity (tapas), study (svādhyāya) and devotion (īśvara-praṇidhāna) that explains “how one with a distracted mind can become absorbed in yoga”, as the commentary puts it.66 Ranganathan’s Yoga Sūtra book translates these concepts clearly as “penance”, “study” and “surrendering to the Lord”.67 His accounts of the latter are also conventional, noting: “Īśvara is a term that traditionally in the context of Hindu and Indian thought (including Yoga) has always denoted a personal, theistic god, and is understood as such by other philosophers in the Indian tradition.”68 Hence, there is the option “to continually benefit from divine grace as assistance in the practice of yoga”, since “by repeating the syllable ‘om’, Īśvara or the meaning of ‘om’ comes to live in our lives, thus allowing Īśvara to be our teacher”.69

The new book strips out theism – as well as chanting oṃ – while redefining īśvara as “sovereignty”,70 “the ideal of the right”,71 and “right choosing and doing”.72 One devoted to īśvara is therefore practising Ranganathan’s method, because “Yoga is fundamentally a moral and political exercise of creating space for ourselves as autonomous people.”73 Consequently, “to understand oneself in terms of Īśvara is to understand what people have in common: an interest in their own Sovereignty”,74 and yoga “is simply our choice to be devoted to Īśvara, which breaks down into tapas (unconservatism) and svādhyāya (self-governance)”.75

This bizarre formulation is sourced to Yoga Sūtra 2.1, which says no such thing – all three are parts of a technique to counter mental afflictions and hone concentration. Instead, the theory interprets (or, as Ranganathan would have it, “explicates”) ideas from other sūtras – primarily 1.24, which he translates as: “The Lord is a special kind of person, untouched by afflictions, actions, effects of actions and stores (of latent tendency impressions).”76 So this “special kind of person” (puruṣa-viśeṣa) amounts to the ideal toward which yogis strive. In the new book’s analysis: “Īśvara has a healthy relationship to its past, not being trapped or afflicted by past actions and choices. Īśvara is hence unconservative. And it has a healthy relationship to its future, not being limited by outcomes or psychological baggage. Īśvara hence self-governs.”77

Ranganathan relates “unconservativism” to the “heat production” of tapas, in the sense of “going against the grain”.78 The link between “self-governance” and svādhyāya is less clear. The literal meaning of the term is “personal recitation”, to quote the Vedic scholar Finnian Gerety, “which refers to the daily ‘going over’ (adhi + the root i-) of oral texts with the aim of memorizing and passing on the Veda”.79 The commentary on Yoga Sūtra 2.1 says recitation can be “repetition of the syllable oṃ and other purificatory [formulas] or the study of treatises on liberation”.80 Since the prefix sva refers to doing this oneself, modern teachers often talk about “self-study”, which mutates into “self-understanding”. Ranganathan glosses svādhyāya as “determining one’s own values”,81 and “owning one’s own position”.82

The effect of that sounds libertarian: “In being devoted to Īśvara,” he writes, “I do not have to put energy into what drags me down – namely difficult experiences or other people’s opinions. I rather put energy into being a responsible person”.83 Yet it is framed as an “ideal normative ethical theory”,84 while “imperfect times” require the “nonideal ethical theory” of eight-part (aṣṭāṅga) yoga,85 whose foundational precepts are yamas – five ethical “restraints” to curb misconduct.

“Accordingly,” Ranganathan says, “we ought to first begin by disrupting systemic harm (ahiṃsā) to allow us to participate in the moral facts (satya) that do not deprive others of their requirements (asteya), and respect personal boundaries that allow for learning (brahmacarya) that leads us away from appropriation (aparigrahā [sic])”.86 This turns the vows of ascetics87 – renouncing killing, lying, stealing, sex and possessions – into a social justice slogan. No matter how appealing it sounds, trying to pin it on Patañjali makes little sense – not least since the original commentary calls yogis brāhmaṇas (i.e. Brahmins), which would limit them to being male renouncers from the priestly elite.88

Meanwhile, āsana – the seated position that is nowadays synonymous with sequences of shapes – becomes “occupying the space that one has created via Yogic activism”,89 while the breathing techniques of prāṇāyāma morph into “deconstructing barriers between oneself and the external world”.90 Quite how that squares with the parallel objective of “taking back control of our personal boundaries” is left for the reader to self-explicate.91 As for cultivation of one-pointed focus – Patañjali’s main method – the prescribed contemplations have more to do with thinking than with meditative discipline: “First, we identify a topic of interest with Dhāraṇā, then we allow ourselves to be moved by its implications. This is to engage in Dhyāna. Finally, we come to a conclusion in Samādhi”.92

CONCLUSION

Ranganathan is far from the first modern author to reimagine the Yoga Sūtra. A generation earlier, Ian Whicher blazed a similar trail, calling kaivalya “a state of embodied knowledge and nonafflicted action”.93 This had more in common with yogic teachings in the Bhagavad Gītā, which reinvented renouncing as detachment from outcomes to forge “skill in action”.94 Whicher later conceded that his preferences as a practitioner shaped his conclusions, saying “the Patañjali that Whicher was studying was really Patañjali plus Whicher”.95 However, he immediately papered things over, adding: “That’s okay, because that’s what I think Patañjali would want. You see, we have to include ourselves”.96

It seems difficult not to. Whatever one’s chosen methodology, personal choices shape one’s priorities. The least one can do is acknowledge them. As an example, consider this line from a book by Ranju Roy and David Charlton, which presents key passages from the Yoga Sūtra for modern practitioners. They seek to distinguish their own expositions from what the text says, writing: “Let us take some practical examples to see how we can apply the idea of ‘putting support in place’ – our interpretation of Patañjali’s definition of abhyāsa”, which they separately explain in traditional terms.97

The word “interpretation” would be a red flag for Ranganathan, since he calls that “the narcissism of projecting our beliefs”.98 However, this critique is in fact a projection of his work’s limitations. Had he simply presented an activist framework inspired by the text – as opposed to insisting it came from Patañjali – much of what he discusses might be worth considering. Instead, this is a post-truth book, which blurs the distinction between objective facts and subjective opinions, while also distorting other people’s work. Its use of decolonial language is especially egregious, since its practical effect is to colonise Patañjali, potentially misleading well-intentioned students about what he teaches. Activist practice would be far better served by an honest attempt to explain innovations on their own merits, rather than disguising them with logical contortions.

If you’d like to support Ancient Futures, click to send me some fuel or subscribe below…

One example – among many others – is translation of the precept brahmacarya. Traditional commentaries on Yoga Sūtra 2.30 say it means celibacy. Since few modern readers aspire to be chaste, the concept is reframed as anything from sexual fidelity to consensual non-monogamy – or such circumlocutions as “wise use of energy”. Useful as this might sound today, it is not what the text itself says, so it ought to be identified as such.

Philipp A. Maas, “A Concise Historiography of Classical Yoga Philosophy”, in Periodisation and Historiography of Indian Philosophy, ed. Eli Franco (Vienna: Sammlung De Nobili, 2013), 81.

For an overview, see Shameem Black, “Decolonising Yoga”, in Routledge Handbook of Yoga and Meditation Studies, ed. Suzanne Newcombe and Karen O’Brien Kop (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021), 13–21.

Shyam Ranganathan, Faculty of Liberal Arts and Professional Studies, York University. https://profiles.laps.yorku.ca/profiles/shyamr (accessed November 15, 2024).

Shyam Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy: An Action-Focused Guide to Practice (London: Singing Dragon, 2024).

Ranganathan runs the website http://yogaphilosophy.com and has an active presence on social media, as well as appearing on yoga podcasts.

Shyam Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra (Delhi: Penguin India, 2008).

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 6.

Shyam Ranganathan, “Translating Evaluative Discourse: The Semantics of Thick and Thin Concepts”, PhD dissertation submitted to the Graduate Program in Philosophy at York University (2007), https://library-archives.canada.ca/eng/services/services-libraries/theses/Pages/item.aspx?idNumber=793484822 (accessed November 15, 2024).

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 13.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 14.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 19.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 26.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 15.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 60.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 316.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 26–27.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 81.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 87.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 87.

Translation of Vācaspati Miśra’s Tattva-vaiśāradī 4.22 by Edwin Bryant, in The Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali: A New Edition, Translation, and Commentary with Insights from the Traditional Commentators (New York: North Point Press, 2009), 462.

For a detailed explanation, see Maas, “A Concise Historiography of Classical Yoga Philosophy”, 57–69.

Commentary on Yoga Sūtra 2.20, translated by Hariharānanda Āraṇya and P. N. Mukerji, in Yoga Philosophy of Patañjali (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1983), 180.

From the translation of Sāṃkhya Kārikā 19 by Gerald James Larson, in Classical Sāṃkhya: An Interpretation of its History and Meaning(Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1969), 262.

Shyam Ranganathan, “The Yoga Sutra of Patanjali: A Biography. By David Gordon White. Lives of Great Religious Books. Reviewed by Shyam Ranganathan”, Philosophy East and West, vol. 66, no. 3 (2016), 1046.

Ranganathan, review of “The Yoga Sutra of Patanjali: A Biography”, 1048.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 103.

Neither Apte nor Monier-Williams lists “volition” as a meaning of cetanā. However, “will” is part of the first definition in the Pāli Text Society dictionary (Pāli being the language used to compile the Buddha’s discourses).

See, for example, Mahābhārata 12.180.25 (thanks to Valters Negribs for the reference): “They say that possession of consciousness is the quality that characterises the jīva and that the jīva is itself active and activates all things. They also assert that beyond the jīva is that which knows the kṣetras (bodies), that which originally set the seven worlds of this creation in motion.” Translated by Nicholas Sutton, in Mahābhārata: Mokṣa Dharma Parvan, vol. 1 (Oxford: Hindu Studies Press, 2024), 134.

Thanks to Valters Negribs and Dominik Wujastyk for their helpful comments on this.

See Yoga Sūtra 1.3, 2.17, 2.20 and 4.23.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 305.

Commentary on Yoga Sūtra 2.40, translated by James Mallinson and Mark Singleton, in Roots of Yoga (London: Penguin Classics, 2017), 83.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 309.

Haṭha Pradīpikā 4.107, translated by Brian Dana Akers, in The Hatha Yoga Pradipika (Woodstock: YogaVidya.com, 2002), 111.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 20.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 20.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 104.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 64.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 94.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 99–100.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 88.

Ibram X. Kendi, How to Be an Antiracist (New York: One World, 2019), 9.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 88.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 88.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 88.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 28.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 65.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 40.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 88.

Āraṇya and Mukerji, Yoga Philosophy of Patañjali, vii.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 127.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 156.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 113–17.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 30.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 17.

Philipp A. Maas, “Pātañjalayogaśāstra”, in Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Vol. 7: Supplement, ed. Knut A. Jacobsen (Leiden: Brill, 2023), 144.

Maas, “A Concise Historiography of Classical Yoga Philosophy”, 69.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 109.

Pradeep P. Gokhale, The Yogasūtra of Patañjali: A New Introduction to the Buddhist Roots of the Yoga System (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020), 46.

The commentary accompanying Yoga Sūtra 3.21, which describes invisibility, ends with the words etena śabdādyantardhānam uktam (saying the same method can prevent being perceived by other senses). Some translations read this as a separate sūtra 3.22.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 240.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 240.

To quote Kurt Leland’s Rainbow Body A History of the Western Chakra System from Blavatsky to Brennan (Lake Worth: Ibis Press, 2016), 75: “…if [cakras] are associated with the rainbow colors, the endocrine glands, and psychological qualities (not to mention gemstones, planets, and so on), this is a Western system.”

For more details, see Mallinson and Singleton, Roots of Yoga, 175–78.

Commentary on Yoga Sūtra 2.1, translated by Mallinson and Singleton, Roots of Yoga, 25.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 130.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 24.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 101.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 23.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 63.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 72.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 82.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 103.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 57.

Ranganathan, Patañjali’s Yoga Sūtra, 97.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 103.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 20.

Finnian M. M. Gerety, “Between Sound and Silence in Early Yoga: Meditation on Oṃ at Death”, History of Religions, vol. 60, no. 3 (2021), 236.

Commentary on Yoga Sūtra 2.1, translated by Mallinson and Singleton, Roots of Yoga, 25.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 146.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 150.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 123.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 23.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 24.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 24.

The earliest reference – in the Jain Ācārāṅga-sūtra (2.15) – says “the ascetic Mahāvīra taught the five great vows” as “I renounce all killing of living beings… all vices of lying speech… all taking of anything not given… all sexual pleasures [and] all attachments.” Translation by Hermann Jacobi, in The Sacred Books of the East, vol. 22, ed. Max Müller (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1884), 202.

For more details, see Philipp A. Maas, “Der Yogi und sein Heilsweg im Yoga des Patañjali”, in Wege zum Heil(igen): Sakralität und Sakralisierung in hinduistischen Traditionen?, ed. Karin Steiner (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2014), 73.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 108.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 108.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 108.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 123.

Ian Whicher, The Integrity of the Yoga Darśana: A Reconsideration of Classical Yoga (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1998), 171.

Bhagavad Gītā 2.50, translated by Winthrop Sargeant, in The Bhagavad Gītā: Twenty-fifth-Anniversary Edition (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2009), 135.

Raj Balkaran, host, and Ian Whicher, “The Integrity of the Yoga Darsana”, New Books Network (podcast), April 13, 2021, accessed April 14, 2021, https://newbooksnetwork.com/the-integrity-of-the-yoga-darsana.

Balkaran and Whicher, New Books Network (podcast).

Ranju Roy and David Charlton, Embodying the Yoga Sūtra: Support, Direction, Space (London: YogaWords, 2019), 94.

Ranganathan, Yoga – Anticolonial Philosophy, 28.

Listening during a walk in nature rather than reading the text I encountered some difficulties in getting the terms right as the intonation of several if not many actually well known subjects (i.e. one example “Purusha” being spelled [purua] ) sounded rather strange.

So if this is AI reading it needs to get taught a bit more of Indian philosophy 🙃 no critique just a bit of improvement suggestion 😉

Nice work Daniel. Thanks.