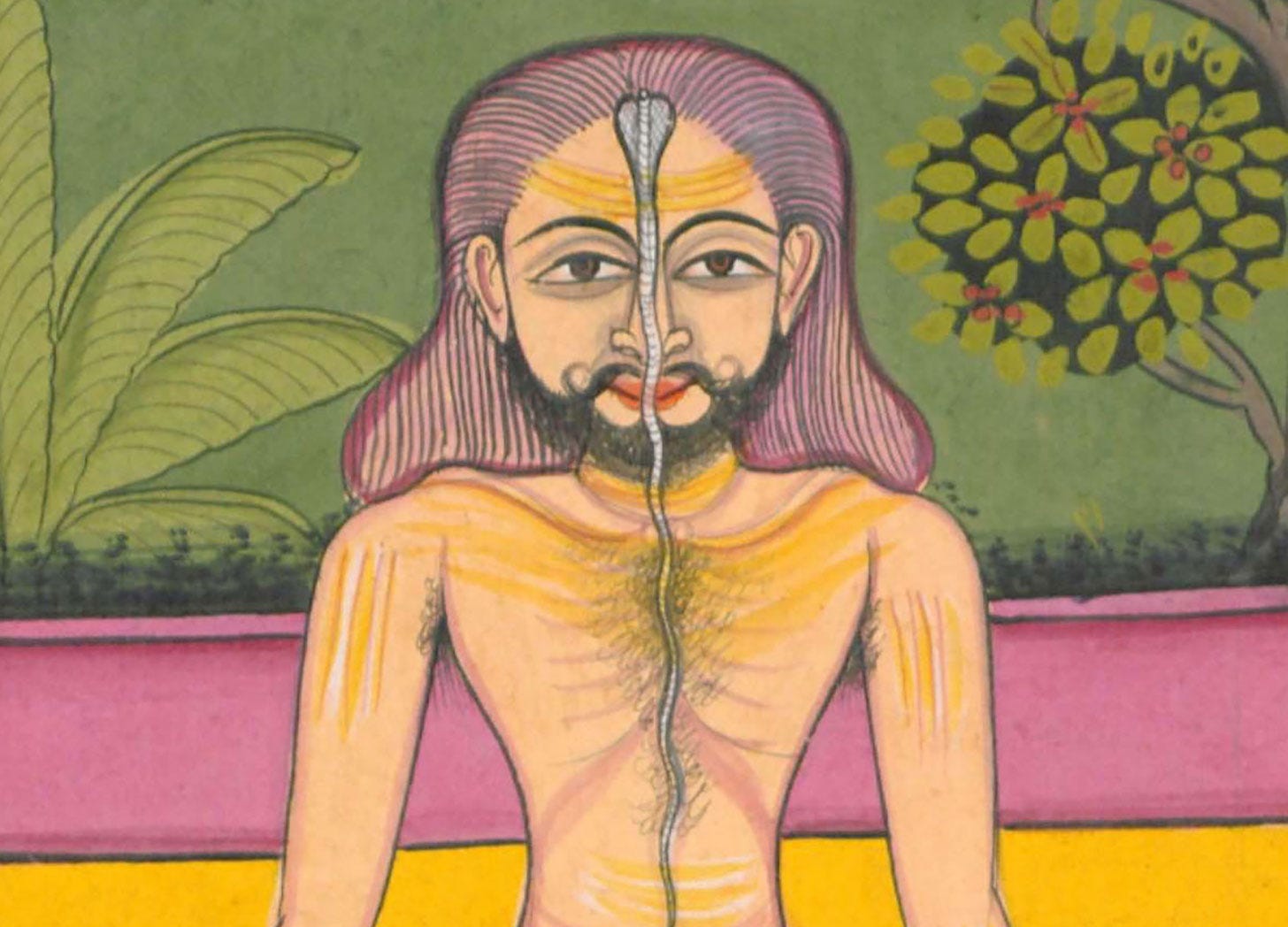

Traditionally, physical methods of yoga seek to move things upwards. Medieval texts describe techniques for making breath and other forms of vital energy ascend a subtle channel in the centre of the spine, with the ultimate goal of dissolving the mind.

Most modern teaching has other priorities – from physical and mental well-being to performing contortions. There might be a focus on raising awareness, but older ideas about manipulating semen are less often mentioned – though they inspired inversions such as headstand and shoulder-stand.

According to yogic anatomy, a moon in the head stores the essence of life, which drips down to be burned by an abdominal sun, causing ageing and death. Texts connect this process with multiple substances, but since many practitioners were celibate men, the most common is bindu, or semen. “The knower of yoga should preserve his semen and thereby conquer death,” says the fifteenth-century Haṭhapradīpikā (3.88).

Turning upside down is a fail-safe method, placing “navel above [and] palate below” in “a divine act that tricks the mouth of the sun” (Haṭhapradīpikā 3.78–79). Others include genital suction, enabling yogis to prevent ejaculation, and to succeed in practice “even when living without inhibitions” – i.e. disregarding celibacy (Haṭhapradīpikā 3.83).

Discussing this with female students can get a bit awkward. Although the text says women can use the same method, it’s unclear what it means to manipulate rajas – the female equivalent of bindu, which usually indicates menstrual blood. Even if it refers to sexual fluids, they don’t have the same reproductive function, so exploring these passages often leads to questioning the overall merits of upward propulsion.

Instead, there might be benefits to getting more grounded in contemporary priorities. But would that mean detaching yoga from earlier roots? Not necessarily. The aim of my teaching is to integrate both by exploring how to bridge potential gaps between traditional principles and modern objectives.

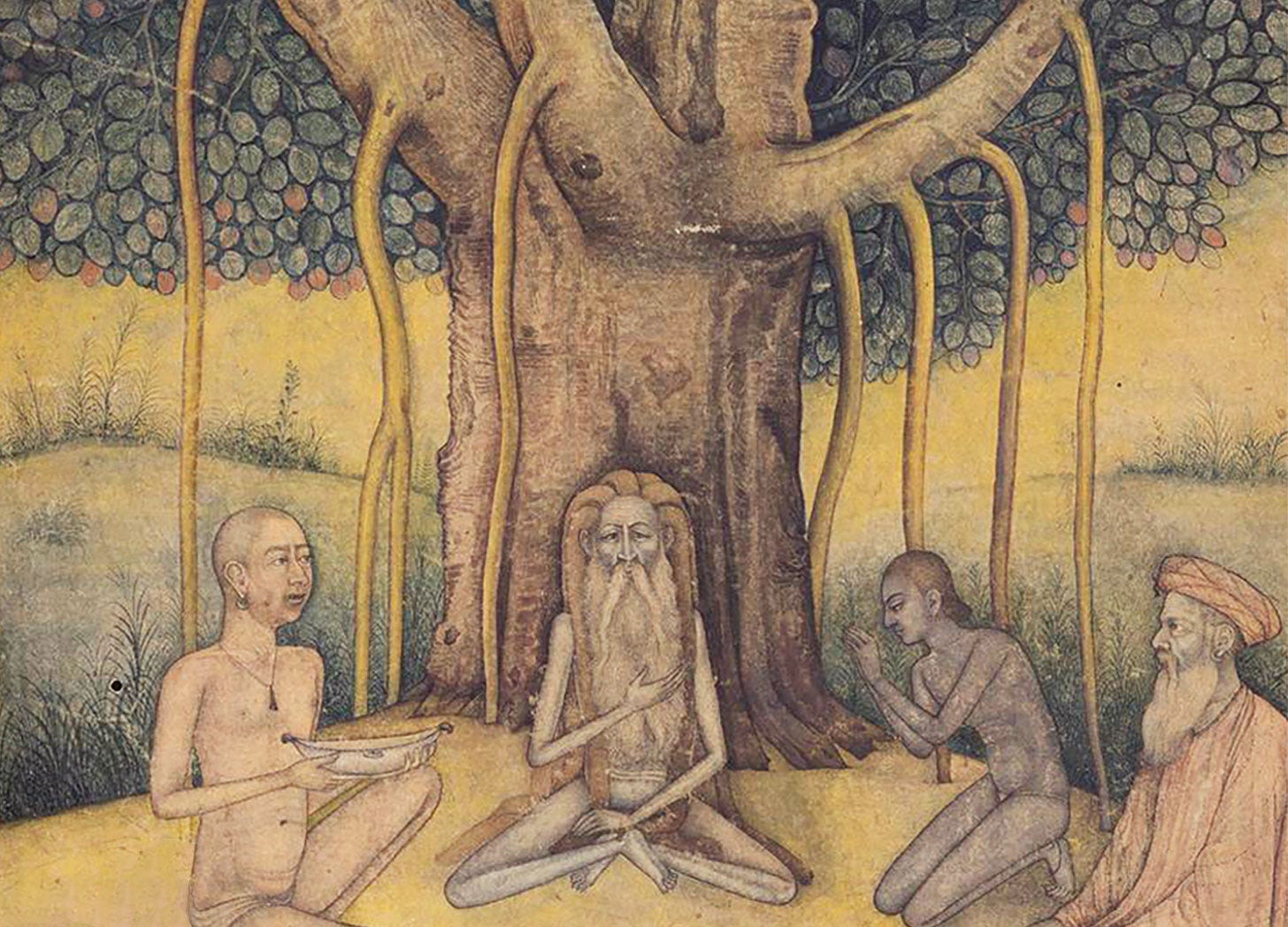

In that sense, I find it helpful to think about trees, whose networks of roots sustain whole ecosystems. Another useful image is the banyan (ficus benghalensis), with its aerial roots that spawn new trunks and branches.

There are also other downsides to “up”. As discussed in a podcast last year with Mariana Alessandri, the philosophical emphasis on light as a liberating metaphor looks down on life’s shadow sides, obscuring the insights that lurk in “dark moods”. And an earlier article described the “love and light” approach to difficult experience as boiling down to “pretend it’s not happening”.

Fixating on enlightenment – or elevated states – can all too easily mean turning away from the world as it is, which sounds like the opposite of yogic ideas about acceptance and contentment. And while there are benefits to seeing things clearly, that’s not easy to cultivate. It’s often the product of striking a balance between mental extremes of agitation and dullness, or confusion and ignorance.

That’s basically the framework of yogic texts based on Sāṃkhya philosophy, which describes these tendencies in terms of three qualities known as guṇas. The clarity of sattva emerges from skilful engagement with polarities of over- and under-activity, rajas and tamas (not to be confused with the rajas above, although both are derived from a root meaning “redden”).

We’re going to be reflecting on all of these questions in practical ways on a weekend retreat at the end of September. The theme is “embodying knowledge” and our aim is to integrate timeless teachings with modern objectives. Find out more via the button below – it’s a great opportunity to gather in-person with a diverse community! If you have any questions, just send me an email…

* For a year-long immersion in yogic inquiry, join us on The Path of Knowledge *

If you like what you find here, and want to support it, please consider paying to subscribe

I think your argument is based on the more populist view of sadhana that was based on Woodroffes commentaries on late mediaeval texts like the sat-chakra-nirupana which then got incorporated into the philosophical slants espoused by modern yoga practitioners.

However, most Classicql Tantrik Darshans have always maintained that there is no distinction between matter and spirit, it’s all the same substance. And kundalini can flow both ways. Enlightenment is not an ascendancy, it’s the recognition (pratibijna) of the Nondual nature of reality right in this moment.

Put another way, the lowest tattva, earth, contains the 35 others implicitly within it.

I don’t mean to be overly scathing but I believe that your blog, whilst being well written, reveals only one facet of the diamond of sadhana.

Thanks for posting. 🌺