Twenty years ago this month, I quit my job as a foreign correspondent for The New York Times. It’s a long story – it wound up as a book – but to keep it brief, I got high and freaked out while my colleagues hyped a bogus case for war.

The Balkans, where I was stationed, fell off the map after September 11, 2001. There was little space to write about anything – let alone to say that Bosnia’s fragmentation showed that no amount of troops or wishful thinking put broken countries back together.

My bosses at The New York Times were true believers in “nation-building”. They saw in it a blueprint for remaking societies across the Middle East. As one of them told me: “the West has put so much energy into teaching people to care.” Therefore, my job was to keep writing updates on how local bigots didn’t follow the script.

Meanwhile, the script for invading Iraq was taking shape. In the summer of 2002, an elite opinion-former filed a report from Afghanistan, warning that it “may come as a shock to Americans” that the “entire war on terror is an exercise in imperialism”. But he stressed that this “doesn’t stop being necessary just because it becomes politically incorrect.”

A few weeks later, the foreign editor sent out a memo on the first anniversary of The Crime That Changed Everything (including standards of evidence for saying Iraq had illegal weapons, links to al-Qaeda or the means to attack the United States). “To judge by the President’s plans,” he mused, “the first half of next year may be busy…”

Staff scrambled for scoops on “the President’s plans”. The most infamous was Judith Miller, who urged me to report that Serbia was selling Saddam Hussein “an advance UAV that is capable of carrying ‘hundreds of klg. of material’: — chem, bio, nuclear”. Her sources were unnamed “officials” in the Bush Administration, who used her to foghorn propaganda from the Times front page. “The first sign of a ‘smoking gun’,” one of her most incendiary stories claimed, “may be a mushroom cloud.”

Said officials duly seized on their creations. “It’s now public,” Dick Cheney thundered on a talk show, while George W. Bush and Condoleezza Rice made “mushroom cloud” a ghoulish catchphrase. By the time Colin Powell held up his vial of white powder at the United Nations – making a “powerful” and “sober, factual case” for war, to quote The New York Times – I’d pretty much checked out.

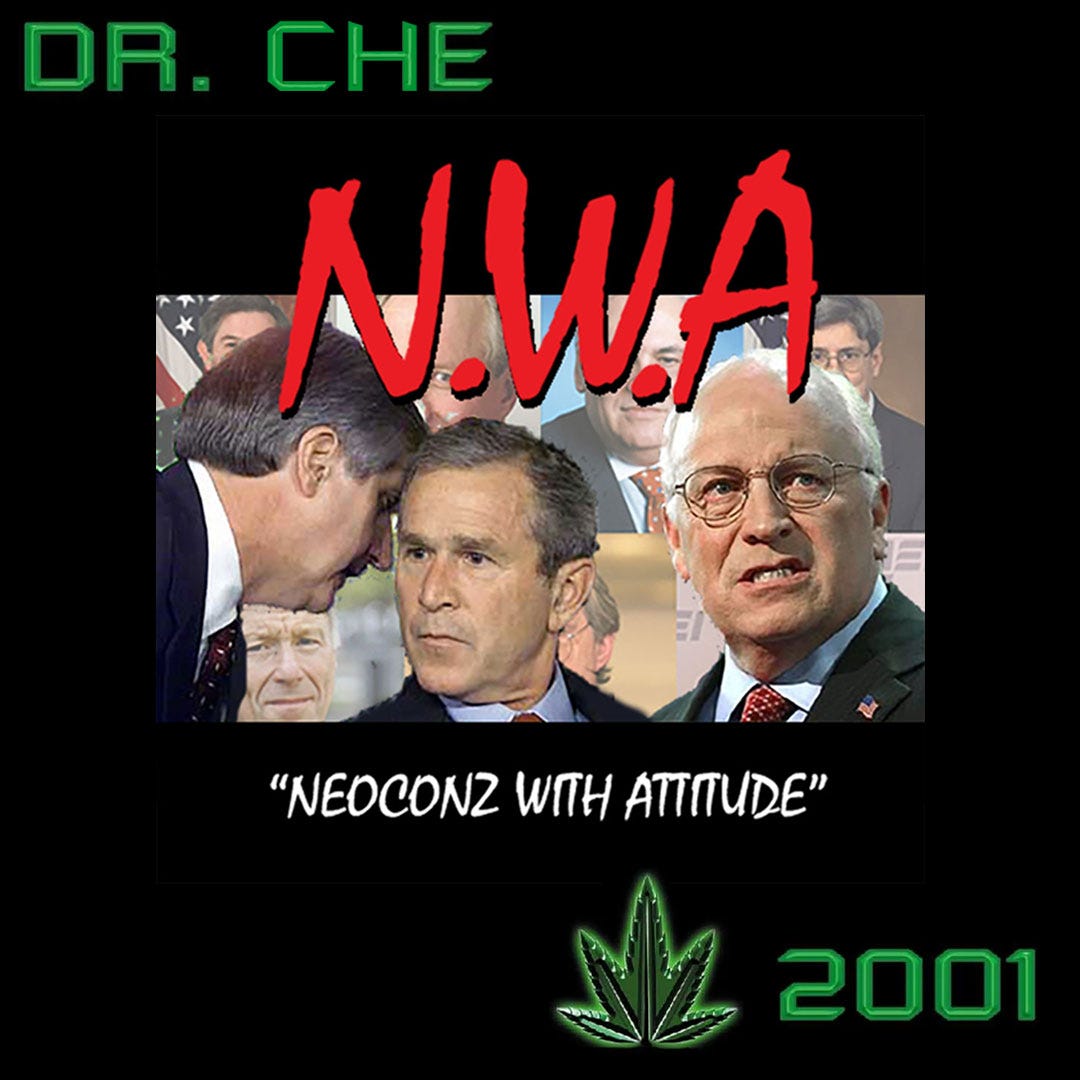

Chain-smoking powerful hash, I’d dreamed up plans for a summer of love on Big War Island in Belgrade. Staging a festival seemed a lot more fun than trying to get ahead at The New York Times. Aged 28, I lacked experience – I’d been hired a few months earlier as a “contract writer” – and had no chance of filing something critical about the push for war. So I resigned and started remixing lyrics from gangsta rap.

America was under assault from the Neoconz With Attitude, and Dick Cheney was the sinister doctor with the tunes: “Y’all know me, still the same O.G. but I been low-key” since the first Gulf War. While most of us “Forgot About Che”, he’d been pulling the strings: “Got it fixed wit’ the studios and they all full of hacks, who wanna kick ass in Iraq, for the oligarchs skulkin’ in back of my House like cronies…”

I mean, how blatant could it get?

I told ’em all — all them phoney liberals

Who you think controls ’em all?

Now you wanna run around talkin’ ’bout fun

Like we don’t need guns —

How’d you think we sold ’em all?

Cuz I play offense?

Now all I get is hate mail all day

About my violence?

What? Cuz I been in the lab wit’ a pen and a pad

Tryin’ to cook the damn’ evidence?

I ain’t havin’ that, this is the millennium of Aftermath

It ain’t gonna be nothin’ after that

So give me one more crack at Iraq and fuck rap

You can have it back.

Yo, where’s all the mad rappers at?

It’s like a jungle in this habitat

But all you bitchin’ Hitchens

Learned I got fixed wit’ tricks

Since yo’ whimperin’ at Richard Nixon.

The following years were frustrating. I expanded the raps into a 90-minute cartoon screenplay titled Dubya Money in God’s Casino – a musical equivalent of Team America: World Police. I even sent it to Eminem, who played Bush to Dre’s Cheney (“Peacenik preachers, left-wing teach-ins, you can’t reach me, my mom can’t neither…”). He didn’t reply, and it failed to win the 2004 Final Draft Big Break Screenwriting Contest.

I also failed to find media outlets for lengthy screeds about the media’s shortcomings, or funding from foundations to launch a broadcaster modelled on a mix of Democracy Now! and Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting (though I did film this clip in 2006 for a BBC competition). To create my own platform, I printed a fake Financial Times, combining satire with critique that was later republished in the British Journalism Review.

These efforts felt futile – in part because I hoped to atone for my own shortcomings, about which my memoir was “brutally honest” (to quote my agent). I’d felt ashamed of abandoning my career without seriously trying to oppose the war – however futile that might have felt too. Attempts to revive it as a TV producer fared badly. No one wanted to talk about unconscious bias towards those in power, so I promptly quit again.

In the end, I renounced my ambitions, becoming a yoga bum. Within a few years, I’d let go of that too, returning from India to study an M.A. in yoga history. That got me teaching, which spawned a new book, but yogic ideas can be hard to embody. Should one be detached, or take radical action? How does one counter unhelpful tendencies?

Those sorts of questions are what I’m exploring in new writing. I’m also making my peace with the self-aggrandisement, self-destructive urges and self-flagellation that lurk in the shadows (as seen in this flashback). Forgiveness feels a lot healthier than clinging to shame…

If you’d like a signed copy of A Rough Guide to the Dark Side, you can order one here.

Amen to an end to self-flagellation!